Learning to Key-Value-Store from Scratch

in Projects / Machine learning on Machine learning

In the life of every Machine Learning researcher, there is a moment when datasets get out of hand. For me, this moment appeared when I have accumulated about 70gb of text data and needed a way to access it efficiently. Especially since you cannot fit this much into your regular computer memory. When providing data for training an ML model, it is easy to stream the data from the disk. However, more advanced operations, like sorting texts by length or querying sentences with specific words, are not available.

The professional approach is to load all the data into a database. This is what I originally intended to do. But the thought of setting up a database service everywhere I want to run my projects seemed daunting. Instead, I decided that I want something that does not require a server, and focus first on simply storing the data.

Iteration 1

One doesn’t have to go far to find the simplest solution in Python’s standard package, named shelve. The limitation is that there is a non-zero chance of key collision. So I started adding the data

import shelve

storage = shelve.open("storage_file")

for ind, text in enumerate(dataset):

storage[str(ind)] = text

Surprisingly, it took such a long amount of time that I decided to scrap the idea of using this package. I believe it is well suited for some other purposes, but not mine.

Iteration 2

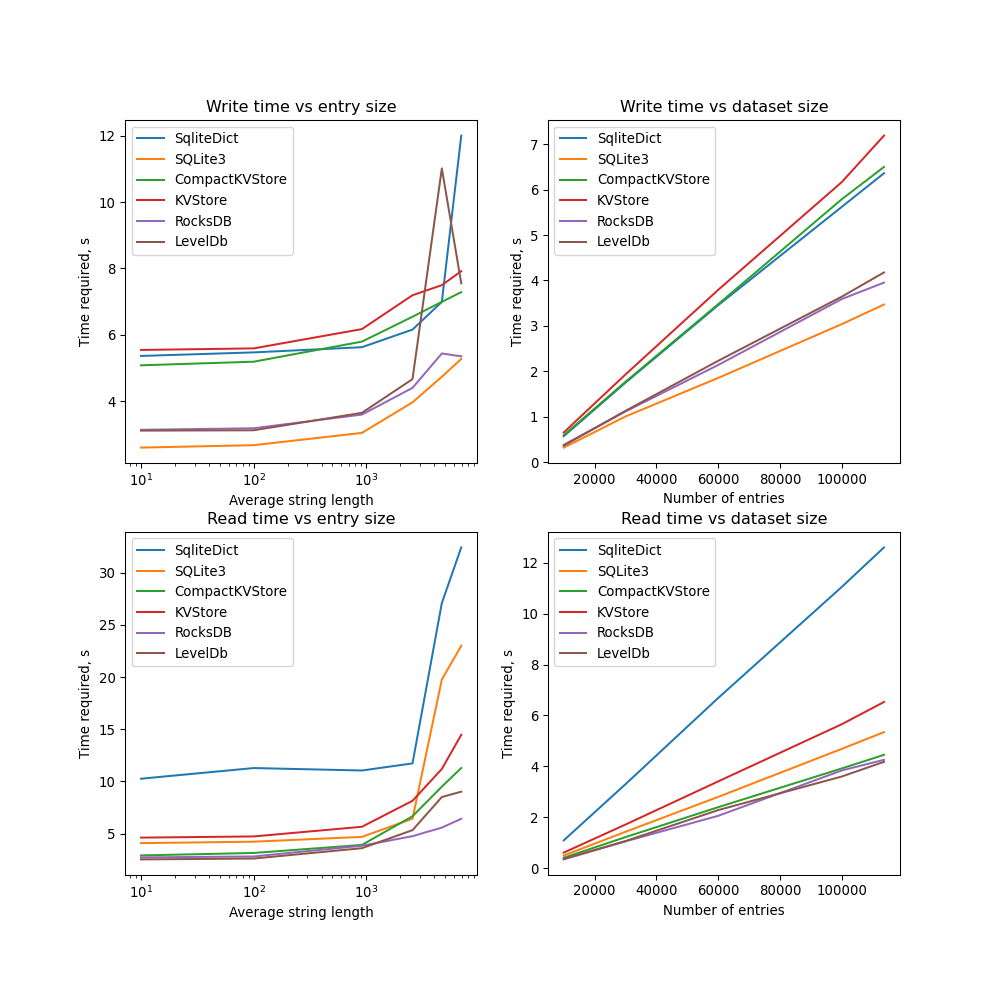

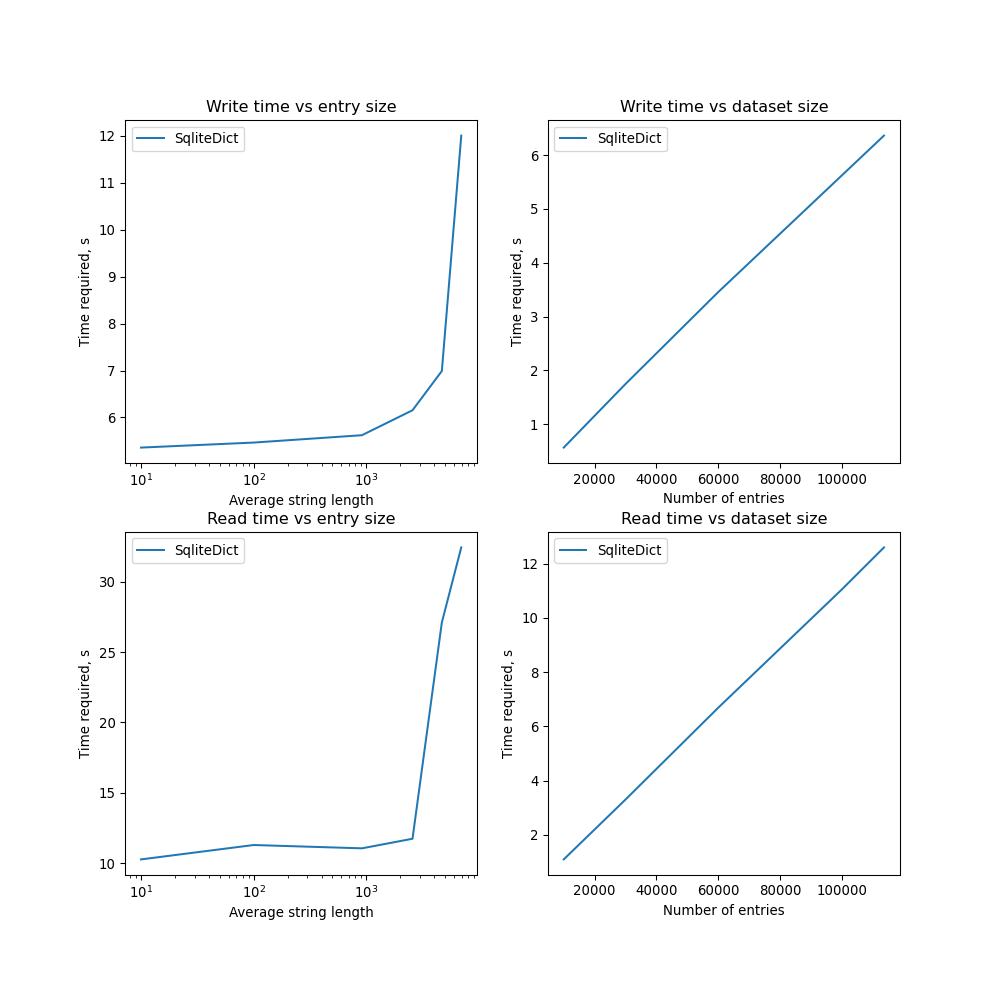

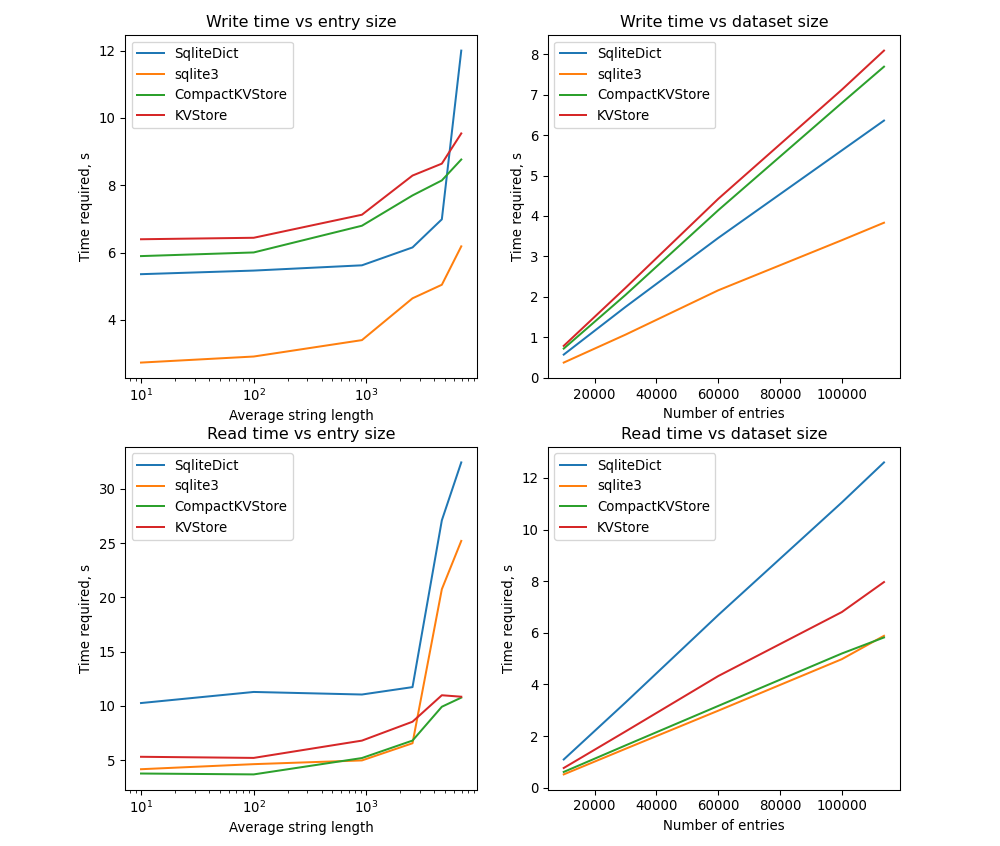

The next best thing that I could find was SqliteDict. Its storage is backed by a SQLite database. I’m testing two aspects of the storage: performance with respect to the dataset size, and the performance with respect to the average size of a stored entry.

from sqlitedict import SqliteDict

storage = SqliteDict(f'storage_file', outer_stack=False, autocommit=False) # additional options for performance

for ind, text in enumerate(dataset):

storage[str(ind)] = text

storage.commit()

It seems that performance decreases rapidly when entry size becomes large. Need to test additional methods.

Iteration 3

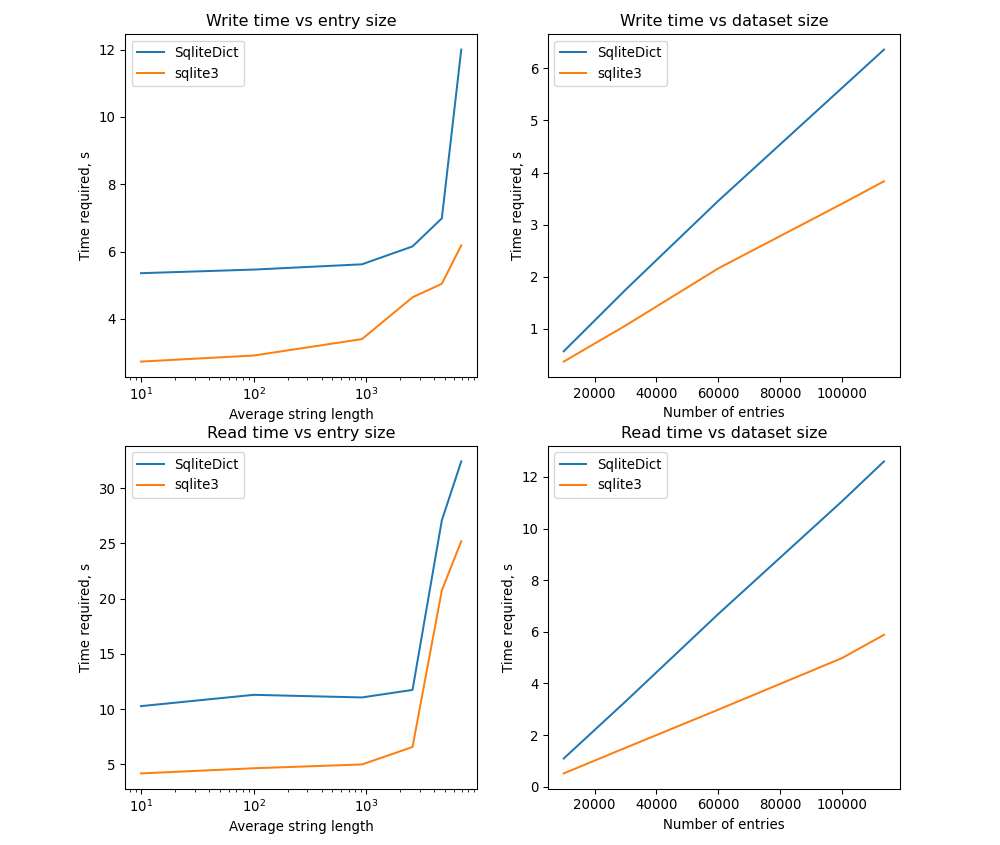

I assumed there is some overhead from all the additional features implemented in SqliteDict, and decided that it is a good idea to test the simplest implementation of a SQLite backed mapping.

conn = sqlite3.connect(f"storage_file")

cur = conn.cursor()

cur.execute("CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS [mydict] ("

"[key] TEXT PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL, "

"[value] TEXT NOT NULL)")

for ind, text in enumerate(dataset):

cur.execute("INSERT INTO [mydict] (key, value) VALUES (?, ?)",

(str(ind), text))

conn.commit()

cur.close()

conn.close()

While there is some improvement, there is still a drop in performance for long entries.

Iteration 4

It seems that a fast on-disk key-value storage is not a low-hanging fruit. But there is still a chance. mmap allows accessing information stored on disk efficiently. It acts as a file that one can write into, but also access different locations in that file using index. The core idea is to write new objects into the file, keep track of the locations where these objects were written, and then access those objects using mmap. The most primitive implementation has the following form

from mmap import mmap

from collections import namedtuple

entry_location = namedtuple("entry_location", "position length")

# writing into mmap

file_backing = open("storage_location", "ab") # open in binary append mode

entry_index = {}

for ind, text in enumerate(dataset):

serialized = text.encode("utf-8") # encode string into bytes

position = file_backing.tell() # get current position in the file

written = file_backing.write(serialized) # write into file

entry_index[ind] = entry_location(position=position, length=written) # store into index

file_backing.close()

# reading from mmap

file_backing = open("storage_location", "r+b") # open in reading mode

storage = mmap(file_backing.fileno(), 0) # create mmap opject

ind_ = 15 # acces entry with id 15

entry_location = entry_index[ind_]

position, length = entry_location

text = storage[position: position + length].decode("utf-8")

storage.close()

file_backing.close()

In the best traditions, we have an append-only data storage. When new entries are added, instead of overwriting the old data, the location in the index is overwritten. Need to do vacuuming once in a while if data is frequently overwritten. There is a significant improvement during reads for large entries (at the expense of writing time). However, now there is a new problem. The position for entries inside mmap are stored in a dictionary. Its size will be considerable when many entries are added into the storage. Need to store the index on the disk as well.

Iteration 5

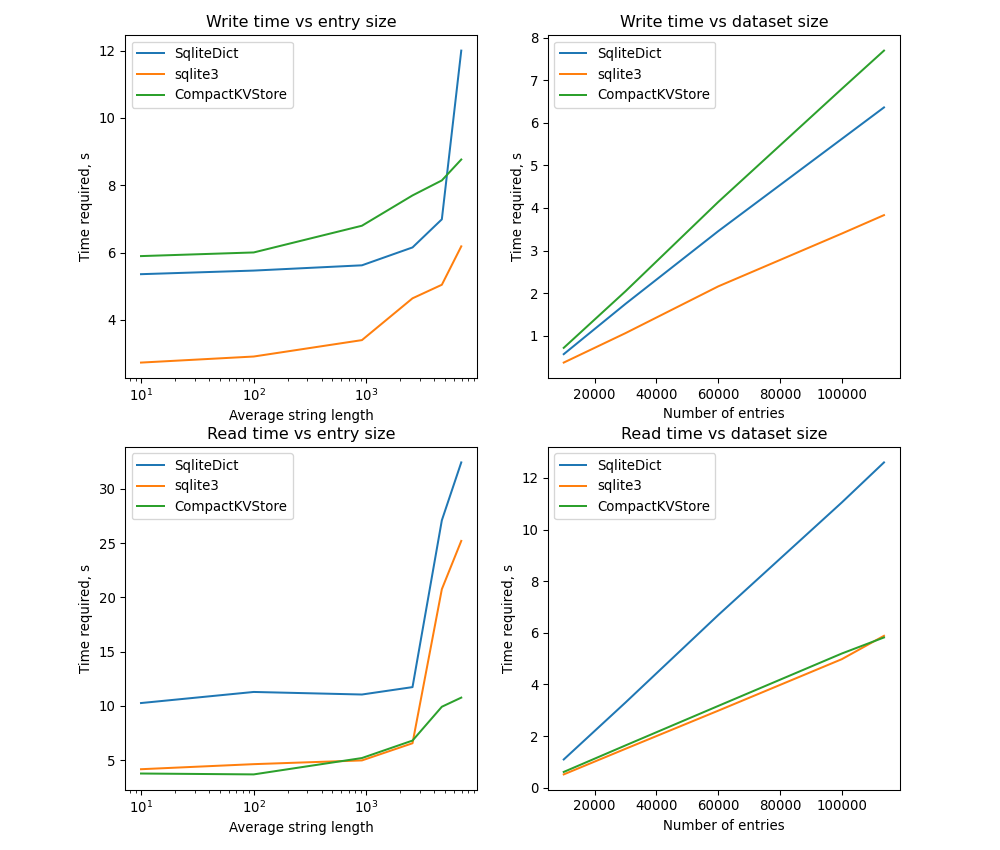

SQLite already proved to be quite efficient when the entry size is small. Fortunately, only two numbers are used to describe entry positions in the mmap file. After combining implementations from Iteration3 and Iteration4, I have obtained the following results

Despite some additional overhead, the read performance is not that bad, while memory usage is small.

Additional Features

Besides basic functionality, I believe the following features should be implemented:

- Automatic switching between read and write modes

- Iterating over keys and values

- Loading and saving procedures (for supporting structures)

- Possibility of using a custom serializer

- Automatic sharding (for file systems with 4gb limit for file, and possibly for multiprocessing access)

- Automatic management of context, since probably only one instance of the same storage should be opened for write at once

- Vacuuming (pending)

The features listed above were implemented in nhkv package.

Alternatives

I’m sure there are better crafted tools for this. A brief search reveals a bunch of them. For my own use case, the reading time of mmap backed storage does not seem to be a bottleneck. And frankly speaking, for accessing datasets, reading is more crucial than writing.

I have also compared the results with LevelDB and RocksDB. These are two serverless key-value stores. They allow to achieve better performance even for larger entry sizes. However, they require installing additional dependencies. An option to use them is implemented in nhkv library (see readme).